Over the course of the term, I have been doing research on the collusion between the Shah of Iran and Western intelligence agencies for the 1953 overthrow of Mohammad Mossadegh, the democratically-elected, secular Prime Minister of Iran. To this day, particularly in Iran but also internationally, there is a significant degree of misinformation and politicization of information regarding the validity of the coup; scholars often linearly attribute the overthrow of Mossadegh to the dissatisfaction with the Shah in 1979, culminating in the Islamic Revolution, but this simplification is problematic and ignores a wide expanse of unrelated factors.

Since I was a child, I have heard various opinions on Mossadegh from various members of my family. To many in Iran, he remains a figure of all that Iran could have been, secular and democratic, with fierce pride in his country and steadfast refusal to accommodate Western oil interests. That he was overthrown by the CIA and MI6 remains a point of deep anger for many in Iran, who, as the current theocratic regime has remained staunchly undemocratic, reflect on Mossadegh as the final gasp of a truly representative Iran. Those loyal to the Shah had starkly different views on Mossadegh, regarding him as a megalomaniac whose obsessive hatred for anything Western blinded him to the extraordinarily negative economic consequences of his pro-Iran policies. For decades, for example, the British Anglo-Persian Oil Company had been extracting oil from Iran’s oil-rich Khuzestan Province, paying pennies to the Iranians for the right to the oil fields, hiring few Iranians, and lying about their sales to avoid compensating the Iranian government. Mossadegh’s nationalization of the Iranian oil industry returned the resources to the Iranian people, but at a significant cost. As he had been warned by the British prior to doing so, the nationalization resulted in an international embargo on Iran’s greatest export. A dramatic decline of the Iranian economy resulted, ultimately resulting in the various machinations of the Shah and Western powers to remove Mossadegh from office, which, despite being extraordinarily dishonest and misrepresented for decades after, were in fact legal under Iranian law. After the Shah regained power, he renegotiated terms with the Western oil companies for a more favorable (theoretically) 50/50 percentage split of oil profits. To an objective outsider, there seems to be enough blame to attribute to each of the parties in this storyline. Nevertheless, the history has been presented by many as a manichaean battle between the Iranian forces of good and evil, with certain segments of the population ascribing Mossadegh to the former and the Shah to the latter (and vice versa). In my RBA, I hope to deconstruct the cults of personality that have sprung up around the two figures and to evaluate the consequences, good and bad, of their actions.

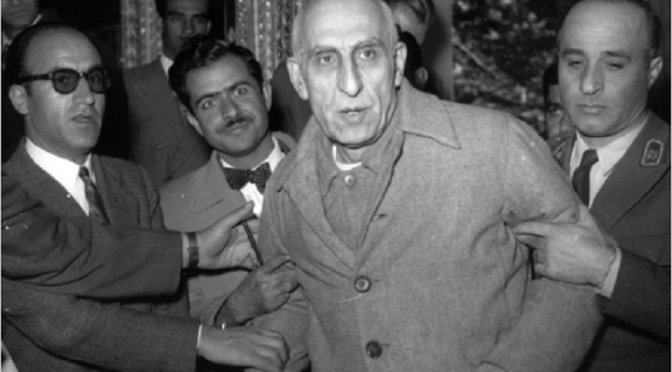

Photograph:

“Mossadegh’s Arrest.” Iran Review, http://www.iranreview.org/file/cms/files/U6HCACBE3KXCAKC3L7ZCAMIQJR3CAKJW8KPCASYBGORCA27RDJWCAJB7SFBCAXH2U0ZCAR63UAKCARU2GPFCA5FL74ICA4JQSBNCA1HNJ35CAOPCTODCA4FZBQ4CAHC8X9JCA0KA9VOCAJCJ4A1(1).jpg