A couple of weeks ago, the Trump administration announced that they were ending the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA) started under the Obama administration to give undocumented minors who were brought to the US at a very young age the ability to gain legal status in the US. Trump had promised that he would end the program and he finally kept his promise despite bipartisan opposition to his decision.

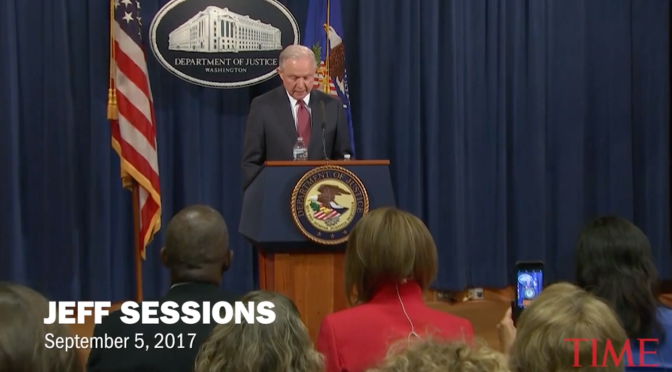

One of the main arguments against immigration is the fact that immigrants are seen as “freeloaders” who benefit from government programs and help despite the fact that they don’t file a 1040 with the IRS. This goes directly against the capitalist idea of getting what you work for. In Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ address dealing with the end of DACA, he draws on this sentiment as an explanation for the administration’s decision.

“The DACA program…essentially provided a legal status for recipients for a renewable two-year term, work authorization and other benefits, including participation in the social security program…”

Many nativists, many of whom make up Trump’s electoral base, believe that the ability to stay and work in the US is being given away to undeserving immigrants. Additionally, the Cold War distinction of American versus Un-American is very clear here as well when immigrants are called “illegal aliens.” The recipients of the DACA program were too young to even form memories when they were brought to the US. This country is all they know and are as American as can be.

Additionally, the Cold War distinction of American versus Un-American is very clear when these Dreamers are called “illegal aliens.” The recipients of the DACA program were too young to be able to decide whether or not they wanted to come to the US or not. This country is all they know and these children are as American as can be. This type of rhetoric is especially apparent in this address but has been a common theme in Trump’s campaign. His campaign was riddled with Cold War-style rhetoric, starting from his very first speech:

“When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best…They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us” (Trump).

The idea of Mexico sending criminals and rapists to corrupt the US brings up memories of the USSR sending its spies to relay information back to the Kremlin and corrupt American “family values.” One would think that this outdated rhetoric would have little effect 30 years after the end of the Cold War, but as the last election taught us, the world is a strange place.

Beckwith, Ryan Teague. “’We Cannot Admit Everyone.’ Read a Transcript of Jeff Sessions’ Remarks on Ending the DACA Program.” TIME, 5 Sept. 2017, time.com/4927426/daca- dreamers-jeff-sessions-transcript/.

Sessions, Jefferson. “Remarks on Ending the DACA Program.” TIME. Remarks on Ending the DACA Program, 5 Sept. 2017, Washington, White House.

Trump, Donald J. “Presidential Announcement Speech.” TIME. June 16 2016